After the gilded metal was discovered on the southwest side of the Ortiz Mountains in the late 1820s, Golden was a place of fevered searching as equipment churned and prominent companies poured money into gold mines.

The striking San Francisco de Asis Catholic Church, among the few structures still standing, was built in the 1830s so the booming gold rush town — its name announcing its reason for being — would have a house of worship. But the gold rush would only last for so long.

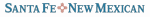

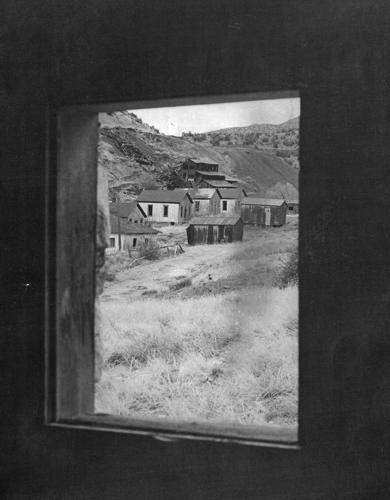

Golden’s gold reserves were depleted, and it steadily shrank, until around 1930 when it became a ghost town — a spot in western Santa Fe County between Madrid and Sandia Park on N.M. 14, once home to a host of rowdy saloons and a stock exchange but now lost to the wind.

New Mexico is known for its deserted towns nestled along boundless highways that have become attractions in the scenic state. According to New Mexico True, operated by the state Tourism Department, the Land of Enchantment boasts more than 400 ghost towns — many made up of little more than aging foundations and the equipment of abandoned mines. But each one has a tale to tell when it comes to its specific demise, a unique range of misfortune that brought it to its knees.

From Golden’s heyday in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, little more than the church and the ghosts of roving prospectors remain in a town that once held 3,000 people at the turn of the century. Once the site of the first gold mine west of the Mississippi River, Golden is now home to about 17 people — a blink and you’ll miss it stop along the Turquoise Trail that connects Santa Fe and Albuquerque through the old mining towns.

In its 175 years as a newspaper, The New Mexican has played a role in whetting the public’s appetite when it comes to promoting and framing ghost towns as alluring destinations, particularly in the Turquoise Trail corridor. It has also chronicled the rise and fall of some of these towns, while penning articles about how the communities now offer cautionary tales about the state’s turbulent history.

How a ghost town is made

A ghost town is broadly defined as a deserted city, or an abandoned settlement, often containing substantial visible remaining buildings and infrastructure from when commerce and industry were vital. For those who pen books about ghost towns, part of this definition is the industry that led to the founding of the towns has moved on, and with it most of the people who once lived there.

Broadly, there are four key dynamics responsible for population loss and the dying off of industry in many of the communities within New Mexico that have become ghost towns, said John Mulhouse, the author of Abandoned New Mexico. In many cases, these towns were where people mined turquoise, silver and gold, but when resources ran dry, nothing could sustain them.

“They all have very interesting stories to tell,” Mulhouse said. “There’s a lot of sort of warm feelings, really warm memories about these places. A lot of people really loved living there, and they loved visiting them and are sad to see them slipping away through socioeconomic forces, really. The emptying-out of rural America, that’s happening everywhere, not just in New Mexico, but it’s pronounced in New Mexico.”

Shifts in technology took a toll as well: Some of the now-abandoned towns are situated along railroads and were water stops back when steam engines needed water to run. But with the advent of diesel in the 1950s, Mulhouse said, these towns began to hollow out, with commerce suffering as the railroad workers fled. One relatively nearby example of this type of ghost town — albeit one that, like Golden, still has a handful of residents — would be Duran, in Torrance County.

Other towns were hopping when the storied Route 66 and other highways ceased to be relevant with the construction of the interstate system. When motorists stopped rolling on past, communities like Cuervo, near Santa Rosa, and Montoya, just west of Tucumcari, became ghost towns.

Then there were places that were settled under the Homestead Act of 1862, which granted 160 acres of public land to any adult citizen who paid a small filing fee, prompting some people to venture out and farm in places like Taiban — now a ghost town in remote and rural De Baca County — out on the state’s eastern plains. It was difficult to grow crops, and severe droughts, as well as the Dust Bowl, drove many homesteaders out of that region.

People’s thirst for these places is enduring as the curious take tours of the ruins and snap photographs. To describe this, Mulhouse likes a Portuguese word, saudade, which means a longing for a time that never existed, encapsulating feelings of nostalgia and loss.

“I think we tend to romanticize the ruins,” Mulhouse said. “I do think people are attracted to the aesthetics of abandonment and the idea that there is something resonant about loss and here is something that used to be thriving and now it’s gone.”

“We kind of apply that to our own lives, too: I think I’m living in this place forever, but am I?” Mulhouse said. “Are my friends going to be my friends forever? Are they going to pass away? Eventually, we are all going to move on, and consciously or unconsciously, that’s kind of the lesson people get from ghost towns.”

Philip Varney, 81, who penned more than 10 books on ghost towns in different regions and states, including New Mexico’s Best Ghost Towns: A Practical Guide, first published in 1981, knows this well. He taught popular courses at the University of Arizona on ghost towns and fashioned a career in writing out of his fascination with the subject.

Varney noted his books always had a “dos and don’ts” section in order to encourage his readers to respect the places they visit.

“People who live in ghost towns are very leery of people who come in with a spade, and you can see why,” Varney said. “One of the simplest things to do is to read about something, so while you are there, they are kind of flattered that you know so much about a place because you care about it. You bothered to come and look.”

Varney knows well the range of sights and sounds present across the varied ghost towns in New Mexico. Golden is one good example. So is Dawson. Thousands once lived in the Colfax County town, its tidy and sprawling cemetery still a testament to this. A minor league baseball team briefly played here.

But Dawson is a potent example of industry gone wrong: The town experienced two dramatic mining disasters, the first in 1913 killing 250 men who arrived to work in the Stag Canyon mine that morning, leaving a mere 23 survivors. Then in 1923, another mine explosion killed 123 miners.

The Turquoise Trail is home to a couple of ghost towns that have seen revitalization and are viewed as interesting places to live, not far from the population center of Santa Fe. In May 1975, The New Mexican ran an article titled “Ghost Town Trail” with a graphic of a haunting-looking wagon and lists of curiosities, shops and things to do in the Turqouise Trail corridor, focusing on Madrid and Cerrillos.

“Some have kind of gone and come back again. Madrid’s an example of a place that was almost a total ghost town at one point in the late ’60s and early ’70s. The pictures are incredible where they show these mining houses that are all abandoned,” Mulhouse said. “Just over time, it’s kind of repopulated. ... That sometimes does happen.”

“I get asked that all the time, ‘Will any of these towns come back?’ ” Mulhouse said. “And it rarely happens, but Madrid is an example of a town that actually did come back from being essentially a ghost town.”

Golden’s heady gold rush

On a Saturday in early June 1902, the owners a mine called Lucky No. 2 near Golden had a contract to sink the mine shaft 25 feet deeper in courting deeper gold reserves. At this point in its history, Golden was living up to its name.

“With the right kind of machinery placed on the ... group of mines, Golden could produce several millions in gold and copper every year,” The New Mexican reported then. “... The owners of the McKinley mine have great confidence that their property will be among the leading gold producers of the country.”

In the same article, the newspaper wrote the Black Prince group of mines, perched on the south slope of the Ortiz Mountains, had enjoyed the best go of it, unearthing a “large amount” of “high grade ore” there.

“Experts claim that there is an unlimited amount of high grade ore to be found in these mountains,” The New Mexican reported, a theory that would not prove to be true.

Business leaders were keen on Golden and sounded off in the pages of this newspaper on this belief in its fortunes. An 1886 story commences: “Golden’s boom continues to spread.” A 1917 headline blared: “Placer Fields of New Mexico better than California.”

A few decades later, things looked very different.

“First there was myth; it sustained those who could not be filled by what they saw or touched, who wished to clothe themselves in sky. These were the dreamers,” reads an article published in The New Mexican in 1973, describing the laborers who lived in mining boomtowns like Golden. “They built the towns which are now playthings of the wind.”